Written by C.E. Chambers and published June 3, 2011.

On April 29, 1997, Charles Brewster, a Special Agent for the U.S. Secret Service in Seattle, Washington, appeared on KGNW Radio. C.E. Chambers was the producer of “Talkline” at the time and this is her recollection of the events that led to Frosty Fowler’s interview with Mr. Brewster. A link to Mr. Brewster’s bio is posted at the end of this article.

Photo 1 (above): Seattle skyline by Julie Van Tosh.

Photo 2 (above): 1997: Charles “Chuck” Brewster who was a Special Agent for the U.S. Secret Service Field Office in Seattle, Washington. The photo is the property of Mr. Brewster.

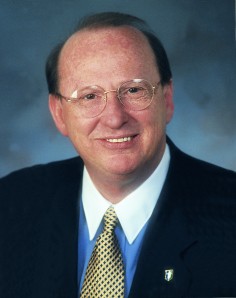

Photo 3 (above): A current photo of Charles Brewster, former Special Agent for the U.S. Secret Service. The photo is the property of Mr. Brewster.

I was channel surfing one day when I came across a sitcom about Los Angeles County Lifeguards that I’d heard about but never seen. Critics had long complained that the action drama — voluptuous young women in skimpy red bathing suits and muscle-bound hunks using state-of-the-art rescue equipment — offered a lot of eye candy but was riddled with ridiculous plots and shallow character development. Unexpectedly, “Baywatch” had become very popular during its second season in the U.S. and was an even bigger hit overseas. Curious as to its appeal, I decided to watch it.

It was well into the first half of the story. It was a beautiful day in southern California. Women in neon-colored bikinis and men in exotic-flowered shorts were happily sunning themselves at the beach, and they seemed to be waiting for someone.

Standing off to the side was a man incongruously dressed in a two-piece suit. He was short and middle-aged and he was not in a party mood. Boy, did he look hot. Suddenly, he started running, kicking up sand as he charged down the beach. He ran in slow motion which emphasized his swinging tie, his taut body and strained facial expression, and he panted and sweated and panted and sweated. Nothing got in his way, not children with dogs, beach umbrellas, or bathing beauties. On he went, gathering speed until, with superhuman effort, he took a giant spread-eagle leap and landed on top of a bomb half-buried in the sand. On closer look, it wasn’t a bomb. It was a child’s high tech-looking toy.

The bikini-clad and bare-chested spectators, who had been watching this spectacle, guffawed and snorted in derision. They turned away in disgust and some threw pitiless glances over their shoulders at the short-haired man sweltering in the business suit.

This embarrassing episode segued to a black stretch limousine that slowly appeared out of nowhere. With flags protruding ostentatiously from its hood, it majestically glided into view and stopped just feet from the expectant beachgoers. It was the President of the United States: William Jefferson Clinton!! A roar resounded from the crowd as he emerged for a brief moment to shake hands with someone. The gleaming, bullet-proof vehicle and its lone occupant slowly drove away to other important destinations.

But wait. Mitch Buchannon, played by actor/producer David Hasselhoff, appeared and stood next to the dejected-looking man in street clothes. They watched the departing limousine together. Then Mitch, who seemed to know the man, turned to him and remarked dryly, “The important thing is you were willing to die to protect him.”

O-h-h-h….I should have known. The goofball was Hollywood’s idea of a Secret Service agent.

That episode of “Baywatch” triggered memories of other times I had seen U.S. Secret Service agents denigrated by the entertainment industry. They were often portrayed as robotic-faced men wearing sinister-looking sunglasses with bargain basement haircuts and colossal-sized communication devices that seemed to grow out of their heads. Even late night comedy shows like “Saturday Night Live” had lampooned them. Kevin Costner’s good-guy portrayal of a former Secret Service agent in the popular film, “The Bodyguard,” had altered somewhat the pervasive negative image that seemed to exist but, true to Hollywood tradition, he wore the nerdiest of haircuts.

As if to underscore the antipathy against the U.S.’s most highly trained Federal agents, a major Washington state newspaper had recently published an editorial that labeled the U.S. Secret Service as “arrogant” or some similar pejorative.

According to a book written by a former FBI agent, even a first lady and her daughter had openly disparaged the Secret Service. In Gary Aldrich’s Unlimited Access, an insider’s account of life in the Clinton White House, a Secret Service agent had informed Aldrich that Hillary Clinton had a “clear dislike for the agents, bordering on hatred.” Inexplicably, she didn’t want the people who were willing to give their lives on her behalf to hover any closer than “ten yards.”

According to Aldrich, this mindset had trickled down to young Chelsea Clinton. Secret Service agents had overheard her describing them to her friends as “personal, trained pigs.”

Why were so many people so snotty about the U.S. Secret Service? By virtue of its name and almost sacred mission, the agency is infused with a mystique that even the people it’s sworn to protect aren’t allowed to penetrate. It’s not driven by public approval or clever marketing strategies, nor should it be. Was this a classic case of stereotyping? How many people who ridiculed Secret Service agents had actually met one? Where was the agency’s spokesperson?

I wanted to hear the Secret Service speak for itself.

At this time of my life, I was the producer of a talk radio program on KGNW AM 820 in Seattle, Washington. Frosty Fowler, the host of “Talkline,” was known as a “dinosaur” in Seattle. In 1965, he had been broadcasting for KING Radio from the Space Needle when a 6.5 earthquake struck western Washington, causing the futuristic-looking structure to sway dramatically from side to side which frightened some people who worked at the site so badly they immediately quit their jobs.

KGNW, where Frosty now worked, was a Christian radio station. However, he had full creative control over his show and between the two of us we offered our listeners guests from all walks of life.

After watching the “Baywatch” episode, I took Frosty aside and asked him, “What’s your opinion of the Secret Service?” He became typically very thoughtful, and finally answered, “I don’t have one.” Frosty held the agency in very high regard, but would have never presumed to know more than what the Secret Service had shared publicly.

I shared with him why I was interested in the subject and he asked, “Well, who should we get on the show to speak about them?”

“The Secret Service,” I replied. Frosty just looked at me. He mulled over my suggestion a moment and asked, “Do you think someone from that agency would be willing to come on our show?”

“Sure, why wouldn’t they?” I answered. “They must have a public relations office…right?”

It was normal to deliberate a few days or even a few weeks before we came to a consensus on some ideas, and this was one of those times. One day, however, as we were holding a conversation over the phone about a totally different subject, Frosty asked me, “Well, shall we do a show about the Secret Service?”

“Yes.”

“How do we get ahold of them?” he sensibly asked.

We discussed the best way to contact the agency, never even thinking at that point to look in the phone book. Soon, however, I just picked up the phone and dialed the White House switchboard.

“White House,” a woman answered crisply. It sounded like she was in a cavern. I visualized an operator who was a few years short of being called an octogenarian, someone perched on a straight-back chair who had served under many administrations.

“Hello, I’m calling from a radio station in Seattle and I’d like a phone number for the Secret Service’s public relations office.”

“Do you want the Washington, D.C. phone number?” she asked cheerfully.

“Yes,” I unthinkingly replied.

It was only a second or two before she came back on the line. I jotted down the number she gave me, thanked her, and hung up.

Stage two. I dialed the number given by the White House operator. R-i-n-g! Someone speaking in a loud voice who seemed to have his mouth pressed against the receiver answered almost immediately. I explained why I was calling and he asked me to hold for a moment.

“You’re talking about a radio station in Seattle?” a male voice suddenly boomed from the receiver. I wasn’t sure it was the same person who had answered the phone.

“Yes.”

“You need to call the Secret Service in Seattle,” he yelled, sounding a little irritated.

“Okay.”

“Here’s the number,” he continued to shout. And he proceeded to relay the information I needed. I thanked him and hung up.

Stage three. I dialed the number in Seattle. A woman answered and once again I explained why I was calling the Secret Service. She was very pleasant; in fact, my impression was that she was unflappable. She asked me to hold, and within just a few seconds’ time, a man curtly said, “Charles Brewster.”

If anything, I was impressed with the Secret Service’s quick trigger finger ability to pick up their telephone calls.

“Hello, I’m calling for Frosty Fowler who’s the host of ‘Talkline’ on KGNW Radio in Seattle, Washington. We’d like to do a program about the Secret Service and we were given your phone number.”

“Why do you want to do a show about the Secret Service?” he barked. A different voice from the guy in Washington D.C. but strangely similar phone manners.

“Well, we thought we’d give you guys — or ladies, as the case may be — some equal time.”

“What makes you think we want equal time?” he asked facetiously.

“Well, that was my terminology…and maybe it was a poor choice of words,” I replied. “But there seems to be some controversy about the Secret Service, and given Hollywood’s influence and tendency to sometimes misrepresent the facts, we thought someone from your agency might like to represent himself for once.”

“So, what’s your agenda?” he countered, spitting out the word.

“We don’t really have one.”

He half laughed and quoted someone whose name I didn’t quite catch. “I attended a media class and [name] taught us that everyone has an agenda.”

“You might be right,” I admitted. “However, to quote David Brinkley,” I gamely continued, “we all have a bias but we can choose to be fair. And that’s why I’m calling you: We want to be fair and offer you – or your supervisor – a chance to go on the air and speak exactly what’s on your mind at this present time.”

“I don’t have a supervisor. I am the supervisor,” he replied, waiting for my reaction.

Ouch.

Charles “Chuck” Brewster, the Special Agent in Charge of the Seattle Field Office for the U.S. Secret Service, turned out to be a very pleasant man. We continued talking for quite a while, and we even shared a few laughs — and they weren’t all at my expense. Employees of the Secret Service are probably trained to size up people in a hurry. I wondered if the initial phone-manners-from-hell was just part of the training: Weed out the wrong numbers and kooks (who would be dumb enough to deliberately irritate a Secret Service agent?) and get down to business immediately because, after all, the Secret Service deals in life-and-death matters 24 hours a day, seven days a week. [Charles had stood guard outside President Reagan’s hospital room after he was shot, and had protected President Carter and Vice-President Bush, among other government leaders, and different heads of state like the Queen of England.]

As I was to learn from Chuck, it’s not uncommon for the U.S. Secret Service to stay out of the spotlight when agents are misrepresented so attention won’t be called to those they protect. I also learned that a significant amount of literature about the Secret Service has unfairly “sensationalized” the agency. People should be skeptical of what they read unless they’ve determined that writers have used trustworthy sources and have done some proper fact checking.

Chuck agreed to appear on Frosty Fowler’s “Talkline” (he had to have a “documented request”) and we discussed what he could or couldn’t say on the air. I had tried to impress him with some research on the subject, having read 20 Years with the Secret Service by Rufus Youngblood and Protecting the President by Dennis V. N. McCarthy.

“Everyone wants to talk about the presidents’ personalities,” he responded with a note of exasperation. “That’s not something I can do.”

Instead, he began to share the history behind the agency. For example, many people don’t know the U.S. Secret Service was started in 1865 to counteract counterfeit money. Poignantly, the Secretary of the Treasury had secured approval from President Abraham Lincoln to create the agency just hours before he was assassinated because currency during the Civil War was “one-third to one-half” counterfeit. The duties of the Secret Service were greatly expanded in 1901 when President McKinley was assassinated.

Something else that Chuck shared with me really struck a chord. He said the only Hollywood full-length feature film that had come close to accurately depicting a Secret Service agent was “In the Line of Fire” with Clint Eastwood. I rented it that night.

Chuck turned out to be an excellent guest on KGNW. By the way, Frosty and I later discovered that the U.S. Secret Service was listed on the first page of the Seattle phone book. Just like Special Agent Charles Brewster had told us it would be.

(Written by C.E. Chambers and published June 3, 2011. She worked for KGNW Radio under her married name.)

NOTE: Charles “Chuck” Brewster retired from the U.S. Secret Service in 1998. He continues to impact the nation, if not the world. He is an ordained minister and was the National Director for HonorBound until 2004. He founded a men’s ministry in 2005 called Champions of Honor and “speaks at various functions and conferences nationally and internationally.” He has won prestigious awards for his work in both organizations. He also formed a company called The Brewster Group that consults on church security issues. Please read:

Read Charles Brewster’s bio here

Read the transcription of Frosty Fowler’s KGNW Radio interview with Charles Brewster here.

Read Frosty Fowler’s bio: Seattle PI July 19, 2006 – “Frosty Fowler Relives His Wild Rides”

Leave a comment